Lessons in Wilderness First Aid

In April, staff from the Research & Conservation Department closed the office for two days and embarked on an intensive wilderness first aid course. As collectors of plant and fungal specimens, seeds, and other types of ecological data, we frequently find ourselves working in the wilderness.

Typically lacking clean work spaces, safe drinking water and access to emergency services, the wilderness can be an unpredictable environment to work in. To become better equipped to work in such an environment, we invited Ben and Caitlin from Longleaf Wilderness Medicine to guide us through their 16-hour WFA course. Read on to learn our main takeaways from this training.

Know who you are exploring with

Before heading out on a trip, it is important to take note of each team member’s allergies, regular medications, pertinent medical history and emergency contact information.

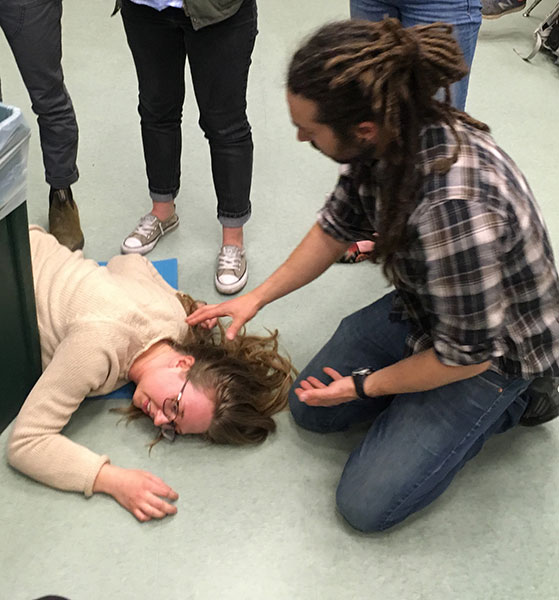

Let’s say Margo is on your seed scouting team and, in the middle of a scouting trip, you find she has passed out behind the tree. Did she pass out because she ran into the tree? Maybe she passed out as a negative reaction to her new, regular medication. Did she fall and hit her head on a rock because of her recovering knee replacement? Maybe she’s slipping into anaphylactic shock because she is allergic to bees and was stung moments before.

Knowing that Margo has not had any joints replaced, takes no regular medication and is not allergic to bees helps us eliminate three of these options, better preparing us to inform medical personnel of Margo’s state when they arrive. If we are unsure of Margo’s allergies, regular medication or pertinent medical history, access to her emergency contact information points us towards someone who knows more and can help medical personnel establish a treatment plan for Margo.

Act within your scope

If your medical expertise is limited to washing and dressing a scrape, drinking water when feeling dehydrated or taking an ibuprofen or two after a minor injury, those services are the best (and only) services you can offer to someone in an emergency.

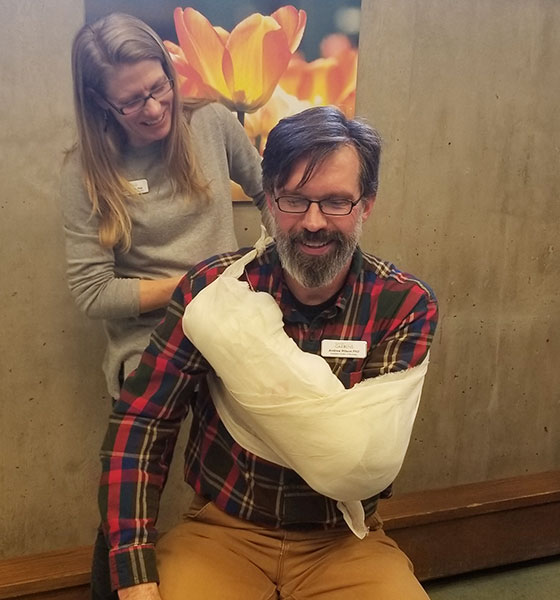

Let’s say Jenny and Andy are collecting mushroom specimens from Mount Evans and Andy trips and falls over a rock, fracturing his forearm. Jenny has recently completed her wilderness first aid certification and, in doing so, learned a variety of emergency medical skills including scanning for bleeding and bodily injuries, casting and splinting.

Having just witnessed the accident, Jenny uses her new skills to locate Andy’s injury and check for other signs of bodily trauma. When Andy is ready, Jenny casts and splints his fractured forearm, making it easier for him to hike down Mount Evans towards safety.

Would Andy be smiling if an untrained person attempted to examine, cast and splint him? Probably not, as taking those actions without sufficient training could potentially worsen his injury. Act within your scope to avoid making a bad situation worse.

Keep a stocked first aid kit

A good first aid kit will include antiseptic prep pads, band aids, gauze pads, medical tape and ibuprofen. A great first aid kit will include a few more supplies, some which might not be so obvious.

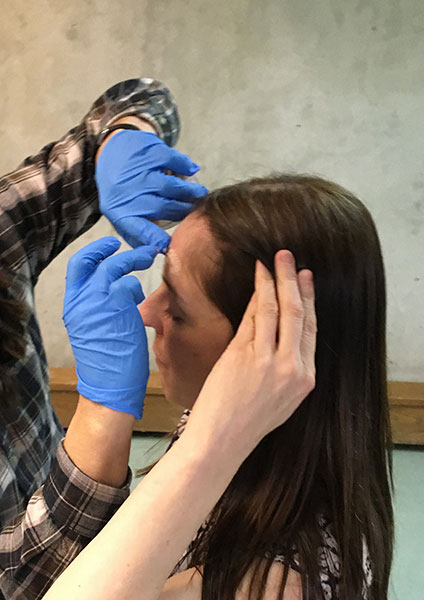

Let’s say you and Chrissy are collecting plant specimens when she accidently cuts her forehead with a hori hori Japanese gardening knife. You want to clean and dress Chrissy’s wound, but your hands are dirty from collecting and the hand sanitizer you have probably won’t take care of the dirt and grime in between your fingers and underneath your nails.

Gloves are an excellent first aid tool that you can use to make this next step safe for both you and Chrissy. Wearing gloves not only allows you to avoid contaminating Chrissy’s wound – it also prevents you from coming in contact with her blood or other bodily fluids.

Other non-obvious supplies to include in your first aid kit include tweezers for removing splinters, stingers and other debris; scissors for cutting tough gauze and bandages; a safety whistle for signaling distress; and a pen or pencil for taking notes on a person’s condition after an accident. Keeping a well-stocked aid kit will can reduce the severity of most emergency situations.

These are far from the only lessons learned from our 16-hour wilderness first aid training. Having undergone this training, the Research & Conservation Department has increased senses of skill and security going into the 2019 field season. Learn more about our training and others offered by Longleaf Wilderness Medicine.

Add new comment