Herbal Medicine and the Influence of the Arabic-Speaking World

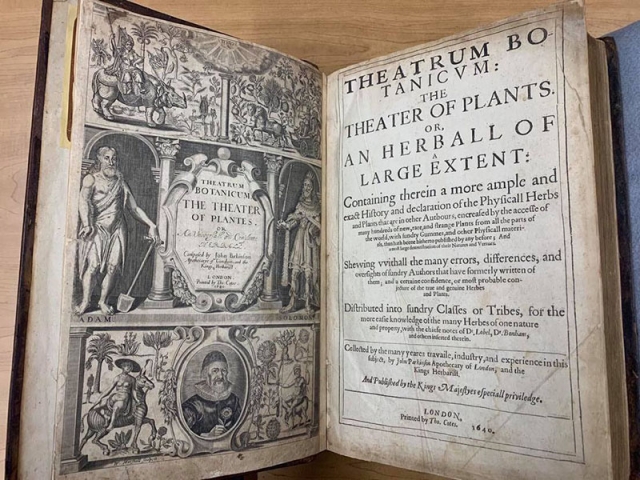

John Parkinson, "Theatrum Botanicum" (London, 1640). Helen Fowler Library Rare Book Collection, Denver Botanic Gardens.

Herbals are essentially early modern products in which plants and their medicinal uses were recorded. Prior to the development of botany as its own discipline, physicians were often the ones most concerned with plants and studied them to find uses for treating patients. Herbals were where those treatments would be recorded. They also became some of the earliest texts printed and circulated after the invention of movable type in the mid-15th century, and their evolution acts as a visual record of the development of botanical illustration as well.

Some of the oldest and rarest books in the Helen Fowler Library’s collections are early European herbals or related texts, whose origins relay an interaction of culture and science that stems from the Arabic language and the Islamic Golden Age.

Avicenna portrait on a silver vase. Museum at BuAli Sina (Avicenna) Mausoleum, Iran. Photo credit: Adam Jones, Canada. Source

The earliest herbal remedies were almost certainly transmitted orally, but written records of them existed from ancient Greek philosophers like Theophrastus (a student of Plato) and Dioscorides. In the 9th century, when the rise of the Islamic world led to a golden age and significant advances in math, science and medicine, Arabic-speaking scientists translated the existing ancient texts from Greek and continued adding to the overall canon of medical knowledge in Arabic.

Ibn Sina (980-1037), known to Europe and the West as Avicenna, is one of the more prominent Persian philosophers who produced an extensive body of work in Arabic; he is known in part for his philosophy concerning compound medicines – as opposed to simples – and the interaction of medicinal properties of multiple plants. His canon of knowledge incorporated and built upon that of the Greeks, Persians, and Indians who came before him, so was studied as the most comprehensive to his date. When the 11th century saw the return of the Greek texts in the West through translations of the Arabic into Latin, Avicenna’s canon was not forgotten. Latin versions of his work continued to be produced into the 17th century.

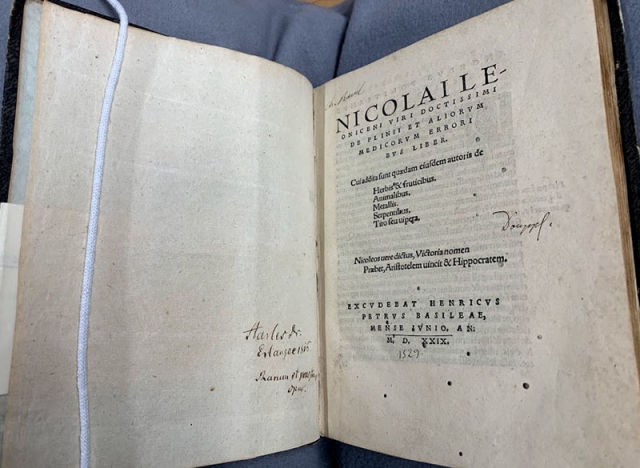

Niccolò Leoniceno, "Nicolai Leoniceni viri doctissimi De Plinii et aliorum medicorum erroribus liber" (Basel, 1529). Helen Fowler Library Rare Book Collection, Denver Botanic Gardens.

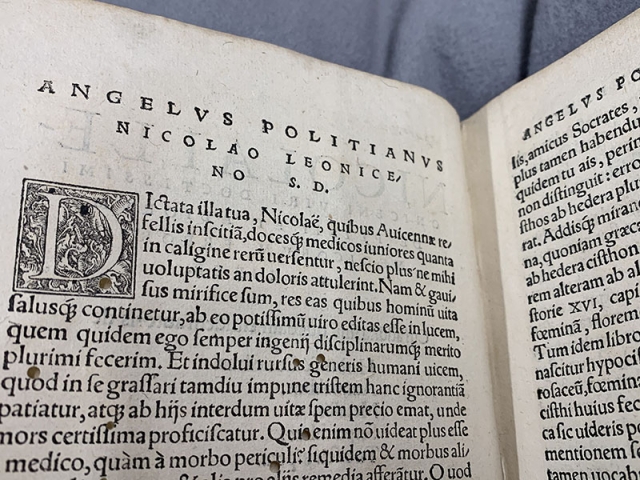

When the translations of Arabic works into Latin began in the 11th century, Muslims were fighting to remain in Italy. The annihilation of Islam in southern Italy in the years following contributed to a very bigoted attitude towards scholarship in the Arabic language, particularly those in medicine. Avicenna seemed to take the brunt of that hatred and was denounced by early Humanists verbally and in writing, some of whom believed Arabic-language works needed to be purged in their entirety from the whole of scholarship. The oldest work in the library’s collections, pictured above, is an edition of a text that initially appeared in 1492 by Niccolò Leoniceno (1428-1524). Leoniceno was one of the more vocal writers against Avicenna, and in his De Plinii et plurium aliorum medicorum in medicina erroribus he details various ways he believes Avicenna “corrupted” medicine of the ancients.

The Latin form of Avicenna’s name can be seen towards the end of the first line of body text.

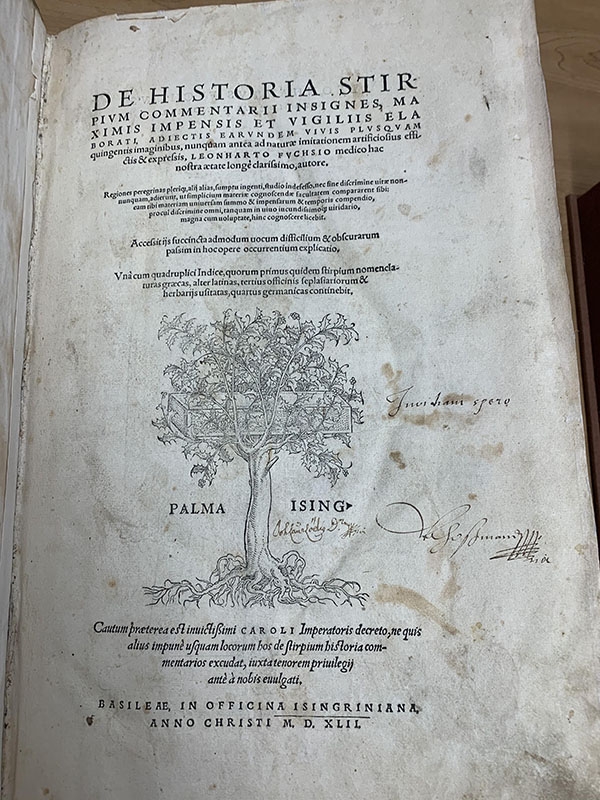

The publication of Leoniceno’s work denouncing Avicenna and medical scholarship produced in Arabic and advocating for a return to the seemingly “pure” texts of the ancient Greeks interrupted the production of new botanical works in his area. Leoniceno, however, was by no means the only one pushing “anti-Arabism,” a term broadly referring to the negative attitude towards anyone producing scholarship in the Arabic language. Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566), one of the German Fathers of Botany, published harsh words against Arabic-speaking physicians – name-calling and using terms like “defiled” to describe the advances scholars made to ancient knowledge during the Islamic Golden Age – prior to issuing his great herbal, De historia stirpium commentarii insignes, pictured below.

Leonhart Fuchs, ‘De historia stirpium commentarii insignes’ (Basel, 1542). Helen Fowler Library Rare Book Collection, Denver Botanic Gardens.

In his herbal Fuchs followed the method set forth by Leoniceno, eliminating any terms transliterated from the Arabic and glorifying the works of the ancients. While the anti-Arabic language sentiments of the early Humanists eventually subsided and the scholarship of philosophers like Avicenna were reintroduced in universities towards the end of the 16th century, hatred always leaves a mark.

The production of new botanical works in southern Italy was temporarily strangled by the chokehold anti-Arabic beliefs held over some early Renaissance Humanists. Scientific advancement suffered during the years in which scholars became obsessed with rooting out any cultural influences from the Arabic-speaking world. Today, the presence of these herbals and texts in the Helen Fowler Library’s collection remind us of the inextricable links that have always existed, and will always exist, between science and culture.

Explore more!

If you would like to learn more about traditional Arab medicine, members of Denver Botanic Gardens can check out our ebook, “Greco-Arab and Islamic Herbal Medicine” by Bashar Saad and Omar Said, right from home. The library also holds books on Persian gardens, as well as floras from other places in the modern Arabic-speaking world like Libya, and we are eager to help patrons learn more about the botanical heritage of the Middle East once we open our doors.

Thank you to a reader whose comments helped me see the need for clarification of Avicenna’s heritage. While the philosopher was Persian, the majority of his medical scholarship was written in Arabic – Arabic being the language of scientific scholarship during the Islamic Golden Age. The early-16th century bigotry was grounded in European distrust of those who spoke or wrote in this language, and those who wrote in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age included a diverse group of peoples including, but not limited to, Arabs. This post has since been edited to be clearer regarding those distinctions.

Add new comment